Rich Hickey’s “Simple Made Easy” is one of the best talks I’ve ever seen. I watched it again recently, after 8 years, but now the part that stood out was the section where he goes into the etymology of “Easy” (timestamp ). It happens very early in the talk, and I just couldn’t think about anything else.

“Easy” is “adjacent”. “Easy” is “nearby”. It’s gotta be one of the best origins of a word. You extend your arm, and grab it. Easy. You walk a little bit, and you’re there. Easy!

Topology is just such a great metaphor for difficulty, or lack thereof. It brings such a clear image to mind. I immediately thought of a big continent with isles surrounding it, and some big bodies of water within it.

Taken from Reddit .

Serendipitous paths

I remembered trying to learn Haskell and functional programming for the first time, following Erik Meijer’s Introduction to Functional Programming . I understood some things, but some things just seemed so alien I wasn’t able to get past them. At that time, I had only a couple of years of experience working as a programmer. I couldn’t even fathom how you could build a program without mutability.

You could say functional programming was just an isle far away from me.

Years later, I gave it another go, this time learning Scala. By then had used list comprehensions in Python, and passed around callbacks in NodeJS. I’d seen the value of JavaScript’s map and filter functions on lists. I followed Functional Programming in Scala

, by Paul Chiusano and Rúnar Bjarnason. This time around things started clicking.

While I didn’t learn Python, NodeJS or JavaScript to become a good functional programmer, in hindsight they made some concepts available to me which laid a bridge between my knowledge and the knowledge I was trying to acquire. They made it easier to understand - they brought me closer to it.

Even though I’d wrapped my head around certain concepts, some others left holes in my map. For example, I still couldn’t really think of monads as burritos or boxes, to name some of the metaphors some people used to try and explain them to complete newcomers to the concept. It took working with JP Vergara

, and lots of patience from him until I finally stopped thinking about them in terms of these paradoxical things which were and weren’t something1 (E.g. Some/ None, Cons/ Nil), and focused on their effect, and their API and not their category and transformations, which is the intuition that really worked for me.

Without understanding what an interface is, or associating a behavior to a class (two things that come from Object-Oriented Programming), this intuition wouldn’t have worked for me. In that sense, OOP brought me closer to the knowledge-land of functional programming.

If, in the beginning, someone had told me to write more JS to learn functional programming, I would have thought they were crazy. This is an interesting thought, because I know many people who are master funcional programmers would agree that learning JS is a waste of time (whether you’re trying to learn FP or not), and I, like many people trying to learn some thing, obsess over the thing, and sometimes this doesn’t work.

I think it makes it evident that knowledge topology isn’t homogeneous across all individuals. A path that works for someone won’t necessarily work for someone else. If someone has a background in Math, then the definition “a monad is a monoid in the category of endofunctors of some fixed category” (from Wikipedia ) might make a lot of sense from the get-go. For other folks it might send them on the wrong direction entirely.

Also, for me, means that paths connecting knowledge-isles aren’t straight lines. This means that depending on what you know (your knowledge continent), you’ll have to keep walking towards the horizon for a little bit until you find a bridge to where you wanna get to.

All roads lead to everywhere

Have you ever played Wikipedia Golf ? It’s pretty fun. It’s even more fun when you’re given totally unrelated start and end pages, like Squarepusher -> Noosphere. The thing is: there’s always a path. All knowledge is interconnected somehow, and the things we don’t know are also connected to what we know, we just haven’t found a bridge or isthmus yet.

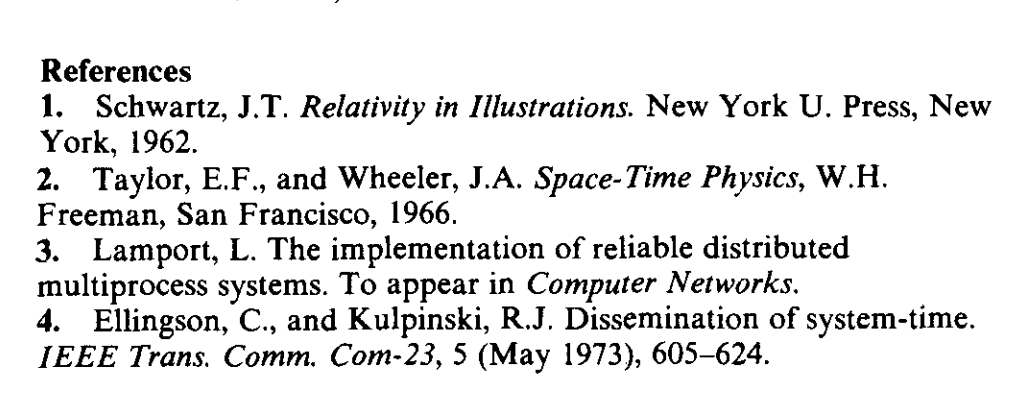

Finding paths to what is known but is unknown to us feels great. And finding paths to something new is how breakthroughs happen. I love the references section in Leslie Lamport’s Time, Clocks and the Ordering of Events in a Distributed System for this exact reason.

It’s VERY sassy, but it clearly reveals how a path can be found between 2 different areas of knowledge. Leslie Lamport had a background in math, and gave a lecture on relativity so he developed a strong intuition about it. It was this knowledge that enabled him to see how it could apply to processes running concurrently, giving birth to logical clocks, which are now a fundamental concept in distributed systems theory.

We spend so much of our lives following expensive guides someone laid out for us. How much happier would we be if we just spent our time finding and following curiosity to the next island?

For many years, I felt guilty about the amount of books I bought, which were definitely more than I could read in a year. I even stopped buying books for a while because they felt like a backlog full of stuff I wouldn’t get through. Then, a year ago, on a whim, I read Nicholas Nassim Taleb’s The Black Swan , which introduced me to the idea of an antilibrary - the set of books you own which you haven’t read yet. Thinking of my unread books as an antilibrary made me reframe how I thought about them, and I’ve since derived so much joy from it. Before, I’d obsess over a subject and try to get many books on it, but after reading a long one or a couple of them, my brain would require a break. Then I’d stop reading for a while because most of the books waiting for me were about the topic I was burnt out on.

Now I actively seek books I know nothing about, and which have no obvious relation to my known interests or my profession. If I need a break from a topic, there’s another waiting, which talks about something else entirely.

Or does it?